Note: If an image ever fails to appear - refresh your page, it really is there

Flags of the American Revolution Era

| Top of Page | Flags before 1776 | Flags after 1776 | Unit Standards and Colors | War of 1812 |

American Revolution Flags Before June 1776

Queen Anne's Flag |

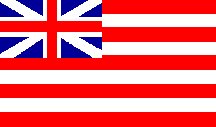

The British Red Ensign 1707

British Red Ensign, also called the "Colonial Red Ensign" and the "Meteor" Flag, was adopted by Queen Anne as the new flag for England and her colonies in 1707.

This was the best known of the British Maritime flags, or Ensigns, which were formed by placing the Union flag in the canton of another flag having a field of white, blue or red. This flag was widely used on ships during the Colonial period. This was the first national flag of the English colonies, and Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown under this flag.

|

English East India Company 1678

British East India Company

after 1707 |

British East India Company Flags c1678-1800

Of course, if you really want to know who caused the American Revolution, the answer is the British East India Company, originally, called the English East India Company, but renamed in 1707. In today's business terminology, because was run by a board representing stock holders, it would be called a "corporation." This was the corporation that the British government was expecting to subdue India, in fact, the company was expected to pay for the soldiers to do so. However, the company ran into so many problems in India that the British parliament had to bail them out by passing laws that required the American colonists to buy the company's tea. Although ships flying this company flag never directly entered American waters, ships transporting their tea, and flying the British Red Ensign, did. This eventually all led to the Boston Tea Party, the Boston Massacre, and the Intolerable Acts.

Since the British East India Company didn't provide any clear instructions to their captains about the company flag design, other than using horizontal red and white stripes, we have flags with nine, ten, eleven or even thirteen stripes and with cantons of varying sizes. Some historians speculate that this flag later influenced the design of the Continental Colors in 1775, but no direct connection has yet been found. Wouldn't it be interesting if the British ship carrying East India Company tea attacked at the Boston Tea Party in 1773 had one of these earlier company flags aboard, and somebody took it to Philadelphia? Pure fantasy, but fun. Click here for more information about the Grand Old Union Flag 1775 on this page, and to learn more information and see more EEIC flags go to the English East India Company on the "Flags of Britain and the United Kingdom" page. |

Schenectady Liberty Flag

Taunton Liberty Flag

Virginia Liberty Flag

Huntington Liberty Flag |

Colonial "Liberty" Protest Flags

Flags with the word "Liberty" on them came to be called Liberty Flags and were usually flown from Liberty poles. They were flags of protest and petition flown throughout the Thirteen Colonies during the five years prior to the outbreak of the Revolution. They proclaimed loyalty to the Crown, but laid claim on behalf of the colonists to the rights of Englishmen, and called for a union of the colonies against current English colonial policies.

Schenectady Liberty Flag 1771

In 1771, a liberty pole was erected the center of the City of Schenectady, New York, as a protest of British policies and interference in the communities' affairs. On top of this Liberty Pole hung a homemade blue silk flag measuring 44 by 44 inches with the word "LIBERTY" in white sewed on one side. Later, this Liberty flag was reportedly carried by the First New York Line Regiment, who largely came from Schenectady, between 1776-1777 during the revolution. Today, it is one of a handful of a pre-revolutionary flags known to exist. It is housed in the Schenectady County Historical Society Museum.

Taunton Flag 1774

The Taunton Flag was one of the earliest of the colonial flags, first raised in 1774 at Taunton, Massachusetts. It was simply a Queen Anne Flag with the words, "LIBERTY AND UNION" sewn onto the red field. The Boston Evening Post reported the incident and the idea caught on. Flags with identical or similar mottos began to appear throughout the colonies soon after.

Virginia For Constitutional Liberty Flag c1775

This flag was reportedly flown from the Williamsburg "Liberty Pole" just prior to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War.

Huntington Flag 1776

The Huntington "Liberty Flag," was flown in the town of Huntington, New York, on July 23, 1776 after the townsfolk received the news of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The flag was later carried at the Battle of Long Island by the 1st Regiment of Suffolk County Militia. It was reported captured by Hessian troops and taken back to Hess (Germany) by the mercenary soldiers. The flag is reported to have survived in Germany until its destruction by fire in a bombing raid during World War II.

|

George Rex Flag (obverse)

according to NY Journal

George Rex Flag (reverse)

according to NY Journal

|

The New York Union (George Rex) Flag 1775

In March, 1775, a Liberty flag was hoisted in New York, bearing the inscription on one side of "George Rex and the Liberties of America," and upon the reverse, "No Popery." The journals say "A Union Flag, with a red Field was hoisted on the Liberty Pole by the Friends of Freedom assembled, and having got in proper Readiness, about 11 o'clock, the Body began their March to the Exchange. They were attended by Music; and two Standard Bearers carried a large Union Flag, with a blue Field, on which were the following Inscriptions: On one Side, GEORGE III. REX AND THE LIBERTIES OF AMERICA. NO POPERY. On the other, THE UNION OF THE COLONIES, AND THE MEASURES OF THE CONGRESS." (New-York Journal or General Advertiser - 9 March 1775)

No image exists of these relatively little known revolutionary flags, and experts debate about the true nature of the flag's designs, with some claiming the flag was a regular Red Ensign, and others claiming it a disfigured Blue Ensign. Here one is shown as a Blue Ensign and one is shown as a Red Ensign.

The problem arises because apparently there were two flags used, one with a "Union" with a red field (with no further description), and one described as a "Union" flag with a blue field with the multiple inscriptions. The term "union," unfortunately, also has multiple meanings during this time period. It could have simply been a "Union Jack" (Kings Colors), or a standard Ensign defaced with writing as illustrated here. These are both speculative reconstructions; It's all guesswork.

|

First Flag of New England

1686-1707

Second Flag of New England

1707-1775

|

The New England Flag and Ensign

The history of the Pine Tree as a symbol of New England predates the European colonial settlements. In eastern Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire and the southern corner of Maine, there lived a nomadic tribe of Native Americans known as the Penacook. "Penacook" is an Algonquin word meaning "Children of the Pine Tree." The Penacook people have been credited with teaching the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony much needed survival skills when the colonists were starving to death during the winter of 1621-22.

A common way to customize English Red Ensigns for ships sailing out of New England was to modify the Cross of Saint George in the canton by adding a pine tree in the first quarter.

After the St. Andrews Cross was added to the St. George's Cross to make the Union Flag in 1707, the New England Flags sometimes showed the British Red Ensign with the tree in the first quarter as demonstrated in the second variant of New England Flags shown here.

The first variant of the New England flag shown here also became a frequent naval ensign for all New England ships prior to 1707. After that, the second variant appeared to gain popularity.

|

Roger William's Flag |

The Massachusetts Bay Colony Flag 1636-1686

The Massachusetts Bay Colony used the British Red Ensign for public ceremonies. In 1636, Roger Williams preached a sermon condemning the "unchristian" shaped cross in the flag as a symbol of the Anti-Christ. Governor John Endicott ordered removal of the St. George's Cross from their flags. Before this was done, however, the Great and General Court of the Colony found Endicott had exceeded his authority and punished him by forbidding him from holding public office for one year.

They also gave permission to any citizen to modify the flag if they wanted, and without exception, most removed all the crosses from their flags. From that time on until sometime about 1685, the unofficial flag of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was red with a plain white canton.

|

Stamp Act Flag

Colonial Merchant Ensign

|

The Sons of Liberty Flags c1765

The history of the Stamp Act flag began in about 1765, when protests of the duties and taxes and stamps required by Parliament began in the colonies. After a protest of the Stamp Act was held under an Elm tree in Boston, the tree became known as the "Liberty Tree," and a protest group known as the Sons of Liberty was formed. The Sons of Liberty continued to meet under this tree, so the British cut the tree down, and the Sons replaced it with a Liberty pole. A flag of nine red and white vertical stripes known as the "Rebellious Stripes" was flown from this pole. The actual date of this flag is speculative.

When the British outlawed the "Rebellious Stripes" flag, tradition tells us the Sons of Liberty created a new flag by changing the direction of the stripes. Three and a half years after the Boston Tea Party, the nine stripes had grown to thirteen horizontal stripes.

This plain red and white striped flag evolved into a naval ensign and was commonly used as a United States merchant ensign in the period from 1776-1800.

|

Nathaniel Page's Flag

|

The Bedford Flag

The Bedford Flag may be the oldest complete flag known to exist in the United States. It's description matches one made for a cavalry troop of the Massachusetts Bay Militia in the French and Indian Wars. Legend claims it is the flag carried by Bedford Minuteman, Nathaniel Page, to the Concord Bridge on April 19, 1775, at the beginning of the American Revolution. There is, however, no real proof, either from testimonials or diaries that mention any flag flown that day by either side, except one by a British officer (Lt. Barker), who reported that British grenadiers chopped down and destroyed a flag and liberty pole standing on a hill near Concord Center. However, he reports that this was done hours before the Bedford's militiamen arrived at Concord.

The Latin inscription "Vince Aut Morire" means "conquer or die." The arm emerging from the clouds represents the arm of God. The original is housed at the Bedford, Massachusetts Town Library.

|

Patrick Henry's 1st Virginia Regiment

Albany Congress Cartoon |

The Culpeper Minutemen Flag

This flag represented a group of minutemen from Culpeper, Virginia. These men formed part of Colonel Patrick Henry's First Virginia Regiment of 1775. Three hundred Culpeper Minutemen led by Colonel Stevens marched toward Williamsburg at the beginning of the fighting. Their unusual dress alarmed the people as they marched through the country. They had bucks' tails in their hats and tomahawks and scalping knives hung from their belts. Their flag’s central symbol was a coiled rattlesnake about to strike, and below it the words "DON'T TREAD ON ME." At each side were the words of Patrick Henry "LIBERTY OR DEATH!"

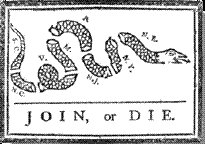

The rattlesnake was the favorite animal emblem of the Americans even before the Revolution. In 1751 Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette carried a bitter article protesting the British practice of sending convicts to America. The author suggested that the colonists return the favor by shipping a cargo of rattlesnakes to England, which could then be distributed in the noblemen's gardens.

Three years later the Gazette printed a political cartoon of a snake as a commentary on the Albany Congress. To remind the delegates of the danger of disunity, the serpent was shown cut to pieces. Each segment is marked with the name of a colony, and the motto "JOIN or DIE" below. Other newspapers took up the snake theme. Some contemporary flag companies are selling a "JOIN or DIE" Flag using this drawing. There is no historical documentation to support this flag's existence.

|

Pine Tree Flag

Pine Tree Flag (variant)

Massachusetts Navy Ensign

Liberty Tree Flag

(modern interpretation)

|

Pine Tree Flags and Naval Ensigns

The term Pine Tree flag is a generic name for a number of flags used by the New England and Massachusetts colonies from 1686 to 1778. The Pine Tree has been a popular symbol of American independence in New England for years.

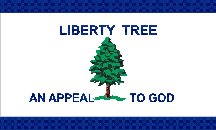

Washington's Cruisers Flag 1775

This flag was used by George Washington on a squadron of six schooners which he outfitted at his own expense in the fall of 1775. This flag was a variation of the New England Pine Tree flag. The Continental Navy, knowing they were up against the greatest naval power in the world, set sail flying a flag with an "APPEAL TO HEAVEN." They needed all the help they could get.

|

|

|

|

|

Washington's Cruisers

(Type 1) |

|

Washington's Cruisers

(Type 2) |

|

Washington's Cruisers

(Type 3) |

Unfortunately, there is controversy over the placement of the words, appearance of the trees and leaves, direction of branches, etc., and it "leaves" us with many possible versions of these flags.

The Massachusetts Naval Ensign 1776-1971

Massachusetts is one of three states with its own naval ensign, the others being South Carolina and Maine. In April 1776, the Massachusetts Navy adopted as its flag (naval ensign) a white field charged with a green pine tree. It also flew this flag over the floating batteries which sailed down the Charles River to attack the British in Boston. This naval militia was active during most of the American Revolutionary War. It was founded to defend the interests of Massachusetts from British forces. The navy used 25 vessels over the course of the war, acting in various roles such as prison ships, dispatch vessels, and combat cruisers. Unlike most other states, the Massachusetts State Navy was never officially disbanded and simply became part of the United States Navy.

|

First Marine Flag

|

The Gadsden Flag

In 1775, Colonel Christopher Gadsden was in Philadelphia representing his home colony of South Carolina at the Continental Congress and presented this new naval flag to the Congress. It became the first flag used by the sea-going soldiers who eventually would become the United States Marines.

This flag first saw combat under Commodore Hopkins, who was the first Commander-in-Chief of the new Continental Navy, when Washington's Cruisers put to sea for the first time in February of 1776 to raid the Bahamas and capture stored British cannon and shot.

|

New York Beaver Flag

(modern interpretation) |

The New York Naval Ensign 1775

In the early days of the Revolution the New Yorkers adopted a white flag with a black beaver for the armed ships of New York. According to legend, the New Yorkers hauled down the British flag in 1775 and raised a plain white flag with a drawing of a black beaver centered on it to mark the occasion. The symbol of the Beaver dated back to the early Dutch settlers of New Netherlands and was based on the long and important role the fur trade played in the development of New York.

Although no documented illustration of the original Beaver Flag has been yet discovered, modern interpretations exist. The beaver is still the official state animal of New York State, and is still seen on the great seal of the City of New York. |

Grand Old Union Flag 1775

British East India Company

after1801

British East India Company

variant after 1801

|

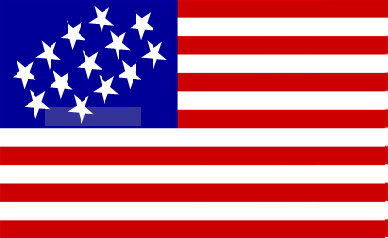

The "Grand Old Union Flag" or Continental Colors 1775

According to legend, one day in 1775 General Washington approached Rebecca Flower Young, a Philadelphia pennant and colors maker, and asked her to make a flag for use by the troops. The flag he designed became known as the Grand Union Flag. Years later, Rebecca assisted her daughter in making an even more famous flag for our country, the "Star Spangled Banner" used at Ft. McHenry.

This flag was never officially sanctioned by the Continental Congress, but was in use from late 1775 until mid 1777, probably because it was very simple to make. All one had to do was sew six white strips over the red field of a British Red Ensign. According to legend, on January 1, 1776, this flag was first raised at Cambridge, where George Washington took command of the Continental Army. He personally paid to equip the first 1000 soldiers under this flag. Although this flag was known as the Continental Colors because it represented the entire nation, in one of Washington's letters he referred to it as the "Great Union Flag" and it is most commonly called the "Grand Old Union Flag" today. ( Click here to learn more )

The Grand Union Flag was also the de facto first U.S. naval ensign. It was first raised aboard Continental Navy Commodore Esek Hopkins' flagship "Alfred" on the Delaware River on December 3, 1775. (See other variants shown as "American Revolutionary War Privateer and Naval Ensigns." below)

Interestingly enough, this was also the flag used by the British East India Company (although usually with less than 13 stripes) after the United States gained its independence. Compare these designs with the original British East India Company Flags. (see above - British East India Company c1678-c1801) Naturally, this all opens the door to debate on how much influence the British East India Company flag and the Continental Colors had on each other.

|

Grand Union Naval Ensign

1776-1777

Brigantine Lexington Ensign 1776

Brigantine Reprisal Ensign 1776

|

American Revolutionary War Privateer and Naval Ensigns

A privateer is a privately-owned warship authorized by "letters of marque" from a recognized national government to attack foreign shipping. The 13 Colonies, having declared their Independence, had only 31 ships comprising the Continental Navy. To add to this, local state governments issued Letters of Marque to privately owned merchant ships which were then armed as warships to prey on British merchant ships.

These "legal pirates" damaged British shipping to the tune of an estimated $18 million by the end of the war, or just over $302 million in today's dollars. Robert Morris, the first American millionaire, became wealthy by privateering, and we know that George Washington owned part of at least one privateer ship.

Apparently the different ships in Commodore Hopkins' tiny Continental Navy were identified by using stripes other that red and white. These ships flew a wide assortment of ensigns and jacks loosely based on various existing Colonial Flags. One of the first Continental Navy vessel was the brigantine "Wild Duck" purchased by Congress and then renamed C.N.S.Lexington in 1776. Another famous American naval vessel was the C.N.S.Hornet. Ever since that time there have been fighting ships named the U.S.S. Lexington and U.S.S. Hornet in the United States Navy, the latest being supercarriers.

Connecticut Privateer Ensign New England Naval Ensign

|

Trumbull's Bunker Hill Flag |

The Continental Flag 1775

Flag of Lincoln County, Maine 1977-present

On the nights of June 16-17, 1775, the Americans fortified Breed and Bunker Hills which overlooked Boston Harbor. Although they had not officially declared their independence, a fight for control of the hills became necessary. When the British advanced up the slope the next day, according to legend they saw a red flag, but we have no real knowledge of which American Flag was actually flown in this battle. But John Trumbull, whose paintings of Revolutionary War scenes are quite famous, talked to eye-witnesses and his subsequent painting depicting the battle displayed the Continental flag as shown here. Many historians think the flag more likely to have been at the battle, if any, was the more common First New England Naval Ensign.

( Click here to see Trumbull painting ) ( Click here to see New England Flag above )

The Continental Flag was the third Flag of New England, and is presently the civic flag of Lincoln County, Maine.

|

False Bunker Hill Flag

|

The Bunker Hill Flag (fictitious)

This so-called "Bunker Hill Flag" with a blue field was the result of an error made by a publisher a couple of hundred years ago. On a flag book this flag, representing New England, was correctly printed with heraldic hatching clearly indicating a red field, but it was hand-colored blue by mistake. This error has lived on to this very day.

I guess it is fitting that we have a incorrect flag for the Battle of Bunker Hill, after all, the battle is misnamed as well! The actual Battle of "Bunker Hill" was fought on nearby Breed's Hill. |

Governor's Conference Flag

|

New England Governor's Conference Flag 1998

I wasn't quite sure where to put this flag, but many times it is sold as a historical flag. The Flag of New England was originally created by K. Albert Ebinger in 1965 to promote the New England region. In 1998, the New England Governor's Conference adopted this flag as the "official emblem of the New England Conference." The governors did not make any claims as to its legitimacy as a historical or authentic flag. It has a blue background with the Saint George cross and pine tree in the canton similar to the fictitious Bunker Hill Flag, but has six stars in a circle on the fly.

|

Moultrie Flag

Town of Liberty, South Carolina

|

The Fort Moultrie Flag 1775

This flag was carried by Colonel William Moultrie's South Carolina Militia on Sullivan Island in Charleston Harbor on June 28, 1776. The "Moultrie" Flag was designed in 1775, and flew over Fort Sullivan (later named Ft. Moultrie) during the battle. The flag was shot away by the British in the battle, but the British were in turn defeated which saved the south from British occupation for another two years.

This became the flag of the South Carolina "Minute Men" and the modern South Carolina State Flag still contains the crescent moon from this Revolutionary War flag.

Another widespread modern version of this flag has the word "LIBERTY" outside the crescent moon on the blue field and is sometimes incorrectly sold as the historical flag. This modern design has been adopted as the civic flag of the town of Liberty, South Carolina, with a few minor alterations of the thickness of the crescent and styling of the lettering. |

| Top of Page | Flags before 1776 | Flags after 1776 | Unit Standards and Colors | War of 1812 |

The First Flag Resolution 1777

On June 14, 1777, the Continental Congress passed a resolution adopting an official flag for the Colonial forces. Unfortunately, it contained no drawings or illustrations of what the flag should look like, just these words.

"Resolved, That the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation."

This led to a wide interpretation by those sewing flags; although hundreds of flags were made, no two were exactly alike.

American Revolution Flags After 1776

Traditional First Flag

|

The Betsy Ross Flag

According to tradition, in June of 1776, Betsy Ross, who was a widow struggling to run her own upholstery business sewed the first flag. Upholsterers in Colonial America not only worked on furniture, but did all manner of sewing work, which for some included making flags. According to the legend, General Washington, Robert Morris, and John Ross showed her a rough design of the flag that included six-pointed stars. Betsy suggested a five-point star because it was easier to make, and demonstrated how to cut a five-pointed star in a single snip. Impressed, the three entrusted Betsy with making our first flag.

This is, of course, a legend started by her grandson 100 years after the Revolution was won, and no proof exists that it ever happened or that the traditional design is of her making. ( Click here to learn more )

|

Striped Pine Tree Flag

(questionable)

|

Hulme's Pine Tree Flag 1776

According to Frederick Hulme (1841–1909) this flag, briefly used in 1776, was derived from the New England Red Ensign (1686-1707) by simply adding 6 white stripes to the existing red field. The design also suggests that it might have been modeled after the Continental Colors of 1775.

His book Flags of the World written by Frederick Edward Hulme in 1896, was considered at the time to be very accurate, but modern vexillological researchers have questioned many of the flag designs illustrated in the book. This particular flag is one such flag and many feel that it most likely didn't actually exist during Revolutionary times, but was a later invention. |

Washington's Personal Flag

(Questionable)

|

George Washington's Headquarters Flag c1777

This flag has been widely called the "personal" flag of George Washington and reportedly made as a headquarters flag in 1777. According to this tradition he used this flag throughout the whole Revolutionary War. Unfortunately, there has been no proven connection that this flag ever belonged to, or was used by, General Washington. Today, a modern reproduction of this "Washington" flag still flies at his Valley Forge Headquarters, but there is no period documentation or proof to support it ever being an actual flag used during the Revolutionary War.

Simply put, the fact that it was discovered in Valley Forge in the mid-20th Century does not prove that it was there in 1777. In fact, the flag lacks a hem on either the fly or bottom sides, which may indicate it was a canton from a larger Stars and Stripes, and it was not designed to fly on its own. It also has no fringe, nor any obvious header that would indicate that it was pole mounted or hoisted. In short, its association with Washington, the Valley Forge winter, the Revolutionary War, and everything else is just unproven speculation and it is very likely Washington never used this flag at all. |

Hopkinson's First Design

(speculative)

|

The Hopkinson Flag c1777

Many give credit for the design of the first Official "Stars and Stripes" to Francis Hopkinson, a Congressman from New Jersey, and signer of the Declaration of Independence. His reported design had the thirteen stars arranged in a "staggered" pattern. Although there is no original example or drawing remaining of this flag, we do have the bill he gave Congress for its design. Congressman Hopkins asked Congress for a quarter-cast of public wine for his work. There is no record of Congress ever paying him.

The flag shown here is the most commonly accepted version, with 6-pointed stars, not 5-pointed ones. Hopkinson may have illustrated a flag with the stars placed in rows of 4-3-4-2. Some favor 5-pointed stars, or rows of 4-5-4, but since Hopkinson's design-sketch has not definitively survived, it is all just speculation. |

Wilson's Brandywine Flag

|

The Brandywine Flag 1777

An interesting bit of erroneous research done on this flag in 1931 resulted in it being mistakenly tied to the wrong Robert Wilson and to the 7th Pennsylvania Militia Regiment, although no actual connection between this flag and the Pennsylvania's regiment existed. Recent research by flag scholar John Hartvigsen indicates that this flag was actually the colors of the Chester County Militia, not the 7th Pennsylvania Militia Regiment. According to Hartvigsen's well-documented research, it was a "Robert Wilson" of Chester County, Pennsylvania, serving as a Lieutenant Colonel with the Chester County Militia, who was responsible for the militia' equipment, and for this flag's survival. Several other members of the Wilson family also served with the Chester County Militia and were present at the Battle of Brandywine.

Since both the traditional account and recent scholarly research assures us that this flag was indeed used at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777 (about three months after the Continental Congress resolution had defined the flag of the United States), no authority questions its status as a military flag used during the battle. In fact, it was Richard Harrison, a direct descendant of Chester County's Robert Wilson, who gave the flag to Independence Hall in 1923, where it is still housed today.

|

Battle of Bennington Flag

|

The Bennington Flag 1777

According to tradition this flag flew over the military stores in Bennington, Vermont, on August 16, 1777. There, the American militia, led by Colonel John Stark, defeated a large British raiding force led by British General John Burgoyne in order to protect military supplies at Bennington. The battle was won when Ethan Allen and Seth Warner, who led the Green Mountain Boys, arrived with cannon and supplies taken from Fort Ticonderoga. Colonel Stark was later promoted to general and after the war was given land in the Ohio River Valley. It is Stark County today. When General Stark died he was the oldest (last) Revolutionary War general.

The traditional version of this story gives Colonial Stark’s wife, Molly Stark, credit for making the flag. She followed the accepted rules of heraldry and began and ended the stripes with white ones. Also according to the rules of heraldry, a star must have at least 6 points. Anything with five points or less was called a "spur."

Unfortunately, some scholars now dispute this whole story claiming that the cotton material and thread used to make the flag dates it more closely to the War of 1812. They claim that it was made by Nathaniel Fillmore (a veteran of the Battle of Bennington) for his son Colonel Septa Filmore and the New York/Vermont militia. It was used at the Battle of Plattsburg (Lake Champlain) in 1814, a battle considered by many as the turning point of the War of 1812. ( Click here to learn more ) |

Allen's Green Mountain Boys

|

The Green Mountain Boys Flag

Ethan Allen and his cousin Seth Warner came from a part of the New Hampshire land grant that eventual became the modern State of Vermont. They commanded a New Hampshire and Vermont militia brigade known as the "Green Mountain Boys." A notable victory of the Green Mountain Boys occurred on the morning of May 10, 1775, when they silently invaded the British held Fort Ticonderoga and demanded its surrender. The captured cannon and mortars were then transported across the snow covered mountains of New England. This surprise installation of some of these on the heights over Boston Harbor enabled George Washington to force the British to leave that important harbor.

On August 16, 1777, the Green Mountain Boys fought under General Stark at the Battle of Bennington. This flag's green field made sense when you realized the Green Mountain Boys carried the flag in the forest. Bright red and white stripes were not very practical there. As in many American flags, the stars here were arranged in an arbitrary fashion. Nevertheless, they signified the unity of the Thirteen Colonies in their struggle for independence.

One final note, the records kept by Seth Warner are fairly complete and according to them his men had little in the way of equipment, so it is possible they never had any flag at all. Some flag historians now believe this flag might have been the regimental colors of a completely different Revolutionary unit (see the Headman Flag) as listed in the mysterious "Gostellowe Return"), but nevertheless, despite these intriguing theories, legend still places the flag firmly in the hands of the Green Mountain Boys.

|

Fort Mercer Flag

|

The Fort Mercer Flag 1777

In 1777, two forts were constructed on the Delaware river. One was Fort Mercer on the New Jersey side, and the other was Fort Mifflin on the Pennsylvania side opposite Fort Mercer. So long as the Americans held both forts, the British army in Philadelphia could not communicate with the outside world or be resupplied. General Howe, the commanding British general in Philadelphia, sent Lord Cornwallis with 5,000 men to attack Fort Mercer, landing them by ferry three miles south of the fort. Rather than let the garrison be captured by the overwhelming British forces, Colonel Christopher Greene decided to abandon the fort on November 20, leaving the British to occupy it the following day. The British then began an assault on the neighboring Fort Mifflin.

This unusual 13 star flag that was flown at Fort Mercer for some unknown reason reversed the normal red and blue colors. |

Fort Mifflin Flag

|

The Fort Mifflin Garrison Flag 1777

The Fort Mifflin Flag was originally a Continental Navy Jack. The defenders of Fort Mifflin borrowed the flag because the navy was operating in the vicinity of the Delaware River forts and it was the only flag the soldiers of the fort could get.

During the 5-day siege of Fort Mifflin, the flag remained flying, despite the largest bombardment in North American history up to that point with over 10,000 cannonballs shot at the fort. At one point the flag was shot from the pole and two soldiers were killed raising it once more. This was the only time the flag wasn't flying throughout the constant barrage. Although the Fort did not surrender to the British, eventually it was evacuated because of the extensive damage and the defenders fled to safety in New Jersey. Today, this flag still flies over the restored fort.

|

Jones' Serapis Flag

|

The Texel or Serapis Flag 1779

On September 23, 1779, John Paul Jones lost his first ship, the C.N.S.Bon-Homme Richard, in battle with the British frigate H.M.S. Serapis. As the Bon-Homme Richard sunk he boarded and captured the H.M.S. Serapis, then sailed the badly damaged prize ship into the Dutch harbor of Texel, where it eventually was turned over to the French. The British Ambassador demanded the ships Sherapis and Alliance, and their crews, be seized as pirates "because they flew no recognized flags," and turned over to them.

The story behind this flag was that our Ambassador to France, Ben Franklin, was then asked what the new country’s flag looked like. A flag based on Franklin's faulty description was then painted for the French court, who officially recognized it. Copies were then sent to various European ports including Texel, where the harbor master showed John Paul Jones the drawing of Franklin’s version of the American flag. Jones had one made and proudly raised this flag when he sailed back to the colonies on the Alliance.

|

Fort Sackville Flag

|

The George Rogers Clark Flag 1779

This red and green striped flag was used by General George Rogers Clark during his attack on the British held Fort Sackville during the American Revolution in 1779. Fort Sackville was a British outpost located in the frontier settlement of Vincennes.

His celebrated capture of Kaskaskia in 1778 and Vincennes in 1779 greatly weakened British influence in the Northwest Territory. Since Clark was the highest ranking Continental officer to operate in the future Northwest Territory, he has often been hailed as the "Conqueror of the Old Northwest."

|

C.N.S.Alliance Flag

|

The Alliance Flag 1779

This was the flag of the 36-gun Continental Navy frigate Alliance, one of finest warship built in America during the Revolution. During the war, the Alliance flew an ensign with seven white stripes, six red stripes, and thirteen eight-pointed stars.

Under Captain John Barry she captured three enemy privateers and three Royal Navy warships during 1781-1783. She carried American diplomats to France for the peace talks, and fired the last shots of the Revolution in an engagement with two Royal Navy warships in 1783. Her final Revolutionary War service was carrying the Marquis de Lafayette back home to France.

|

First Naval Ensign

Colonial Merchant Ensign

|

Traditional First Continental Navy Jacks

The "Don't Thread on Me!" and Rattlesnake Ensign has become a powerful American symbol which tradition tells us was used by the Continental Navy in 1775 and is now being used again by the U.S. Navy in the War on Terrorism.

Although there is widespread belief that ships of the Continental Navy flew this jack, there is no firm bases of historical evidence to support it. We have several fanciful contemporary pictures showing a very youthful Commodore Esek Hopkins (he was actually 58 in 1776), our First Navy Commander-in-Chief, that appeared in Europe during the Revolution that showed flags flying from both the bow and stern of his ships. In some pictures the rattlesnake flag appears, and in others we only have stripes.

In short, there is strong reason to believe that the actual Continental Navy Jack, like the Colonial Merchant Ensign, was simply a red and white striped flag with no other adornment. It should also be noted that the so-called First Navy Jack was probably not a Jack at all, but an ensign. However, by turn of the century the tradition of our navy using the symbol of the rattlesnake with the motto "DON'T TREAD ON ME" was firmly established in American myth. ( Click here to learn more ) |

Saratoga and Yorktown Flag

|

The John Trumbull Flag

American artist John Trumbull painted a collection of paintings for the capitol rotunda, two of which showed this flag. Since Trumbull had been an officer in the Continental Army in 1775, and for a short period was an aide-de-camp of Washington, the assumption is that his paintings are based on his personal knowledge of the people and places he painted.

However, there is debate over the flags shown in Trumbull's paintings since he was not personally at all of the battles and relied on the descriptions of those who were there to compose his drawings. From the general composition and evidence in the canvas, Trumbull painted these picture between 1816 and 1824, but he based his compositions on smaller originals he made in the 1780s and 1790s. (see Photo Gallery #2) and (see Photo Gallery #3) |

John Hubert Flag 1775-1776

|

The Hulbert Flag 1775-1776

In July of 1775 a company of Long Island minutemen under the command of Captain John Hulbert moved to Fort Ticonderoga to assist in the campaign to liberate the Champlain Valley. According to legend this flag was made either in Long Island before Hilbert's company left for Ticonderoga, or during the campaign in the Camplain Valley.

In November the company escorted British prisoners back to Trenton and Captain Hulbert reported on his mission to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, shortly after which the volunteer company was disbanded and they all returned to their homes in January of 1776.

Exactly 150 years later, in 1926, a tattered old flag was found in a house once occupied by John Hulbert. This flag was soon heralded as one of the earliest Stars and Stripes. |

U.S.S. Ranger Flag

|

The First Official Navy Flag 1777-1795

The first official documented US flag had also a staggered star pattern and was used by the navy. On April 24, 1778, Captain John Paul Jones, in command of the U.S.S. Ranger and flying this flag, became the first American officer to have the American flag recognized by a foreign power.

Although very similar to the original Hopkin's flag, this flag replaced the six-pointed stars with the more traditional five-pointed "American" stars. |

3rd Maryland Regiment Colors

North Point Flag 1812

|

The Cowpens Flag 1781 - The North Point Flag 1812

At the Battle of Cowpens General Daniel Morgan won a decisive victory against the British in South Carolina on January 17, 1781. This colonial victory forced Cornwallis to come to the aid of the defeated British forces and led to another costly battle for the British against Nathaniel Greene’s forces at Guilford Courthouse in North Carolina.

The Cowpens Flag, according to legend, was carried at the Battle. In reality, the flag was the regimental flag of the Third Maryland Regiment, and this unit had been disbanded just prior to the battle. Some historians claim that members of the disbanded regiment were reassigned to other units present at the battle, and it was these soldiers who carried their flag, although others claim the flag as one not used until the War of 1812, rather than a Revolutionary flag at all. The most current research seems to indicate that the flag was actually first carried by Joshua F. Batchelor at the Battle of North Point during the War of 1812. Because of this it is also being called the "North Point" Flag today.

( Click here to learn more )

The original flag, complete with bullet holes, is still stored in the State House in Annapolis, Maryland. The famous "Spirit of '76" painting by Archibald MacNeal Willard features the Cowpens flag, not the Betsy Ross design, which is similar.

( Click here to examine the painting. )

|

Guilford Courthouse Flag

|

The Guilford Courthouse Flag 1781

Tradition tells us that this flag was raised over the Guilford Courthouse in North Carolina on March 15, 1781. There, under the leadership of General Nathaniel Greene, the militiamen halted the British advance through the Carolinas and turned them back to the seaport towns. This was one of the bloodiest battles of the Revolutionary War with the British losing over 25% of their troops.

This unique Flag has an elongated canton and blue and red stripes. However, since it was common practice for military units to carry flags that featured common American symbols (such as stripes and stars), but to make them uniquely identifiable for use as their regimental flags, this flag was probably never intended for use as a national flag. Moreover, recent research now dates this flag between 1812-1814, thus making it more likely a North Carolina militia flag of the War of 1812 rather than a Revolutionary War flag as tradition previously believed. ( Click here to learn more ) |

South Carolina Naval Ensign

|

The South Carolina Naval Ensign 1778

According to an article appearing in National Geographics Magazine on historical flags (1917), this was the flag of the South Carolina Navy during the American Revolution. The flag is essentially the same as the Continental Naval Jack, but with the motto "DON'T TREAD ON ME" appearing on the third red stripe from the top, and using stripes with the colors of Scotland (blue) and England (red). Prior to the article this flag was not associated with the South Carolina Navy.

This flag is now being mistakenly reproduced by some modern flag companies with the motto "DON'T TREAD ON ME" placed not on the third red stripe down, but on the second stripe from the bottom where they appeared on the First Continental Navy Jack. Unfortunately, the words don't show up well on the dark blue stripe.

|

Bauman Yorktown Flag

|

The Bauman Yorktown Flag 1781

Within days of the British surrender at Yorktown on on October 19, 1781, an American artillery officer named Major Sebastian Bauman (2nd New York Artillery Regiment) drew a map with this flag pictured on it. It was later engraved by Robert Scot of Philadelphia and published . Bauman had carefully surveyed the terrain and battle positions at Yorktown, at the siege of Yorktown. Bauman had emigrated to America from Germany after service in the Austrian army. During the Revolution, he served in the campaigns in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, and was in command of the artillery at West Point, before joining Washington at the siege of Yorktown. |

Simcoe Yorktown Flag

|

The Simcoe Yorktown Flag 1781

During the battle of Yorktown in October, 1781, this flag flew on the right flank of the American troops. A 26 year-old British Lieutenant Colonel named John Graves Simcoe in command of the Queen's Rangers at Yorktown painted this from his station across the river.

Many flag historians believe that the flag was between Simcoe and his position at Gloucester Point and the sun, thus resulting in the strange colors he perceived. After the war Simcoe went on to become Upper Canada's first lieutenant-governor and probably the most effective of all British officials dispatched from London to preside over a Canadian province. |

| Top of Page | Flags before 1776 | Flags after 1776 | Unit Standards and Colors | War of 1812 |

United States Flags 1783-1822

Including the War of 1812

Jonathon Fowle Flag

|

The Fort Independence Flag 1781

Jonathon Fowle presented this flag to the officers of "Castle William " (later renamed Fort Independence) in Boston in 1781. The first foreign war ship to visit the new United States after the war was H.M.S. Alligator in 1791. She saluted the American flag with 13 guns and the fort returned the salute. The flag is now part of the Massachusetts State House collection.

|

US-French Alliance

|

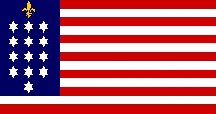

The United States-French Alliance Flag 1781-82

In 1781 and 1782, in honor of the end of the American Revolutionary War and the help of France in that conflict, a special U.S. Flag appeared. It consisted of 13 red and white stripes with a very long (11 stripes long) canton bearing either 12 or 13 white stars and a gold fleur-di-lis. The stars are shown in contemporary illustrations either as 5 pointed or as 6 pointed in rows of three (with a single star below if there are 13) and the fleur at the top. |

Buell Flag 1783

|

The Buell Flag 1783

In 1783, a Connecticut printers named Abel Buell published "A New And Correct Map Of The United States Of North America," in which this image of an American flag was reproduced. Much like Paul Revere, he was an American silversmith and engraver. He engraved a number of maps, including maps of the Florida coast and a large wall map of the United States, the first produced in America after the Treaty of Paris in 1783. .

|

Battery Park Flag (possible)

Battery Park Flag (possible)

British Union Flag

Colonial Red Ensign

|

Battery Park Flags - Evacuation Day 1783

Tradition tells us that John Van Arsdale climbed the greased flag pole in Battery Park (New York City) on November 25, 1783, to remove the British Flag nailed to the pole and raise the new American Flag. Now called Evacuation Day, this event marked the last vestige of British authority in the United States when its troops in New York departed from Manhattan.

Tradition also claims the last shot of the American Revolution was fired the same day by a British cannon on one of the departing ships, whose shot fell well short of the shore, but was still aimed towards the crowd gathered to see the departure. Since no contemporary accounts survive of the event describing the flags involved, it is left up to historical speculation on the star pattern used, or which British flag was removed.

We assume the British flag removed was either the King's Colours (British Union Flag 1606-1649, 1660-1801) or the British Colonial Red Ensign (1707). Experts disagree on which one was used, some argue that King's Colours were normally flown on all British land fortifications at the time. Others argue that in the American colonies the use of the Red Colonial ensign was common on land, especially on coastal forts and other land-based installations. It should also be noted that some 19th Century illustrations do show what appears to be a British Red Ensign being removed, but, of course, the accuracy of these 19th Century illustrations is very questionable. I personally would like to believe that it was the Red Ensign taken down (if there was actually a flag left behind), because the thought that the British military would leave the King's Colours behind to be torn down by the Americans in disrespect, doesn't fit in with my image of British national pride.

As for the US Flag used to replace the British flag, there was no such thing as a "typical" United States Flag in this era, but several designs were fairly popular during this period. One possible version would include a 3-2-3-2-3 horizontal star arrangement, which was common on many U.S. flags of the era. Another version could be a 4-5-4 horizontal arrangement, also popular.

My particular favorite, artistically, would be a version with a circular design of twelve stars in a circle, and the thirteenth placed in the center, also based on several questionable 19th Century illustrations. Several second-hand descriptions of this flag being used do exist, dating from the 1800s, which show the circular pattern of stars with a single larger star in the center, but like the Betsy Ross flag, they are not based on any real documentation or historical evidence. Obviously, the flag image and its size ratio shown here is also speculative. The point is, all of these flags have to be speculative, and unless some as yet undiscovered documentation surfaces, we will probably never know for sure. |

The Shaw Flags

(1983 Bicentennial Reproductions)

In 1983, two replica flags were made for the Bicentennial Celebration, one started with a red stripe and one started with a white stripe. The eight-pointed star was commonly used in the 18th century.

The Shaw Flag 1794

(as shown in Milbourne Watercolor)

|

The Shaw Flags 1783-1784

From 1783 to August 1784, Annapolis served as the United State's first peacetime national capital. There in 1783, General George Washington resigned from the Continental Army. The next year, the Treaty of Paris ending the American Revolution was ratified there. Later in 1786, the city served as the seat of the Annapolis Convention, at which delegates from five states met to discuss proposed changes to the Articles of Confederation.

The Shaw flags were commissioned by the Governor and Council of Maryland to fly in Annapolis while the Continental Congress was meeting. One flew over the State House and one flew over the Governor's Mansion. The flags were provided by John Shaw, a prominent citizen of Annapolis, who is best remembered as a cabinetmaker. He was also an inventor, local assessor, undertaker, state armourer, merchant and City Councilman, and obviously a flag maker.

The Shaw Flag 1794

(Suggested by Milbourne Watercolor)

In the 1794 watercolor by Cotton Milbourne, he depicts a view of the State House's dome with the John Shaw flag flying from it. In the depiction the blue canton runs vertically down the whole left side of the flag, and not, as the in 1983 replicas, across the left corner. Since Milbourne worked in Annapolis in the late 1700s and his drawing of the State House is accurate, it is possible his depiction of the Shaw flag is also as accurate. (It also might have been a little artistic license.) However, on Flag Day 2009, the 1983 replicas flown on the State House were replaced by a Milbourne version. |

Ft. Harmar Flag

|

The Ft. Harmar Flag 1786

The Congress, created by the Articles of Confederation, ordered Fort Harmar built in 1784. Colonel Josiah Harmar was dispatched to the Ohio frontier with orders to discourage illegal settlers from moving into Ohio. In 1785, Harmar ordered the construction of Fort Harmar at the junction of the Ohio River and the Muskingum River, near near present day Marietta. During construction a crude drawing was made of the walls, probably by workmen, which showed this flag. It is of interest because the five-pointed stars, placed in a 4-5-4 pattern, were placed in a diagonal pattern.

Strangely enough, rather than discouraging squatters, the fort encouraged settlement because the settlers believed Harmar's troops would protect them from Native American attacks. In 1789, the Treaty of Fort Harmar, between the United States and the Six Nation federation (Wyandot, Delaware, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomi and Sauk) met with Northwest Territory Governor Arthur St. Clair at Fort Harmar. Unfortunately, the new treaty didn't stop the violence which continued for another six years, until the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The Treaty of Greenville (1795) forced the tribes to give up most of what is now the State of Ohio. |

Beman Flag

(14 Stars - 10 Stripes)

|

The Nathan Beman Flag 1791

This rare flag is one of only a very few known United States flags displaying 14 stars, representing Vermont’s admission as the 14th state in 1791. This flag only had 10 stripes and appears to have been a parade and rally flag that was originally given as a gift to Nathan Beman, one of Ethan Allen’s "Green Mountain Boys," at some time between 1795 and 1815. Nathan Beman assisted Ethan Allen during the surprise attack and capture of Fort Ticonderoga. It was the capture of its cannons and the eventual delivery to Dorchester Heights in Boston that allowed Washington to beat the British and win Boston in the early days of the Revolution.

|

Whiskey Rebellion Flag

|

The Whiskey Rebellion Flag 1794

The first real test of the new Federal Government of the United States was the Whiskey Rebellion. To finance our new country the Federal government imposed an excise tax on distilled spirits. Since coins and currency were scarce, whiskey served as an important medium of exchange. In Western Pennsylvania, farmers refused to pay the tax and attacked the collectors sent from the government. It is believed that this was one of the flags that was used in the brief protest, which ended when our first President George Washington called out 15,000 militia men to protect the tax collectors. There were also reports of striped flags like the Sons of Liberty flag and modified Stars and stripes flags being used in the violent protest over the right of the new national government to leavy taxes.

|

15 Stars - 15 Stripes

|

The Star-Spangled Banner 1795

This flag became the official United States Flag on May 1, 1795. Two new stars were added for the admission of Vermont and Kentucky. This flag was used for the next 23 years, and it is the only flag to ever have more than 13 stripes.

During the War of 1812, Major George Armistead, Commandant of Fort McHenry outside of Baltimore, Maryland, said he "desired to have a flag made so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance" if they attacked. A giant garrison flag (an oversized American flag is called a garrison flag) was made by a Baltimore flag maker named Mary Young Pickersgill, whose mother, Rebecca Flower Young, had made the Grand Union Flag for George Washington. The Fort McHenry Flag was 30 feet high and 42 feet long.

During the war the British attacked and burnt the capital building in Washington, D.C. in August of 1814. The next month the they attacked Baltimore. During the bombardment of Fort McHenry, Francis Scott Key wrote "The Star-Spangled Banner" in honor of the men at Fort McHenry and the very big flag that flew over the Fort. The British failed to capture Ft. McHenry and were unsuccessful on their attack of Baltimore.

( Click here for the words to the poem "The Star-Spangled Banner." ) |

Revenue Service Ensign* 1799

Revenue Service Ensign*

War of 1812 version

Revenue Ensign 1867

* These two reconstructions were drawn by vexillologist Ray S. Morton for his unpublished Early American Maritime Flags & Signals ©1999.

|

Customs Service Revenue Ensign of the United States 1799

This flag has started one of the great urban flag legends of all time after a movie based on Nathaniel Hawthorne's "The Scarlet Letter" was released. Hawthorne's original work of fiction contains a description of an American Customs Service flag erroneously describing it as having 13 stripes and calling it a "civilian" flag. (The real Customs Service flag has 16 stripes, one for each state at the time the flag was introduced in 1799.)

The U.S. Customs Ensign was adopted to distinguish Revenue Service (Coast Guard) cutters from merchant ships at sea and was later flown at custom houses on land. The original Revenue Cutter Service flag was designed by Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott and flew as the emblem of the Custom's Service from 1799 to 1951, when the original design with the eagle and arch of 13 stars across the top of the canton was modified and replaced by a flag with the current coat-of-arms of the United States.

Customs Service 1951 U.S. Coast Guard 1951

The traditional ensign of the United States Coast Guard has also been modified to reflect the changed national coat-of arms and had a Coast Guard crest added to the fly. As it was intended in 1799, the ensign is displayed as a mark of authority for boardings, examinations and seizures of vessels for the purpose of enforcing the laws of the United States. The ensign is never carried as a parade or ceremony standard.

(Click here to find out more) about how these flags began the myth of a conspiracy by the "military/industrial war complex" to elimate the "other" American for civilian use.

|

Free Trade and Sailors Rights

|

"Free Trade And Sailors Rights" Swallow-tailed Pennant 1813

This swallow-tailed white flag inscribed "FREE TRADE AND SAILORS RIGHTS" in blue, summed up what the U.S. saw as the principal issues in the War of 1812. This flag is best known as having flown aboard the U.S.S. Chesapeake when she fought (and was captured by) H.M.S. Shannon on June 1, 1813, and aboard the U.S.S. Essex on March 28, 1814, when she was captured by H.M.S. Phoebe and H.M.S. Cherub off the coast of Chile. However, it also was displayed aboard other vessels as well and is included in an official model of the U.S.S. Constitution outside the Secretary of the Navy's office. |

Commodore Perry's Ensign

|

The "Don’t Give Up The Ship" Naval Ensign

During the War of 1812, Captain James Lawrence, commanding the 49-gun frigate U.S.S. Chesapeake, was attacked off Boston Harbor by the British ship H.M.S. Shannon.

In less than 15 minutes, Lawrence's crew was overwhelmed. Mortally wounded, Lawrence shouted, "Tell the men to fire faster and not to give up the ship; fight her till she sinks!" True to his words, every officer in the Chesapeake's chain of command fought until they were either killed or wounded.

In honor of Captain Lawrence, a group of women stitched the words "DON'T GIVE UP THE SHIP" into a flag that was presented to Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, who commanded a new ship named after Captain Lawrence in the summer of 1813. Perry and the U.S.S. Lawrence went on to capture an entire squadron of British ships in the Battle of Lake Erie, although not before every officer on the ship, except for Perry and his 13-year-old brother, was either killed or wounded.

Lawrence's words became the motto of the U.S. Navy, which has since named numerous ships in his honor, and Perry's flag now hangs in a place of honor at the United States Naval Academy. |

Horn's Easton Militia Flag

|

The Easton Flag 1812-1814

The local legend attached to this flag is that it was displayed on July 8, 1776, for the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence in Easton, Pennsylvania, by Robert Levers. However, in reality, it was the company colors of Captain Abraham Horn's Militia Company from Easton which fought during the War of 1812.

The original survives at the Easton Public Library. ( Click here to learn more )

|

Veteran Exempts Flag

(Interpretation #1)

Veteran Exempts Flag

(Interpretation #2)

|

The Battle of Plattsburg Flag 1814

The Veteran Exempts, commanded by a Captain Melvin L. Woolsey, was a local New York militia company, formed in July of 1812, which was made up of veterans of the American Revolution who were otherwise exempt from military service because of their age. Many of the settlers in upstate New York (and Ohio) were veterans of the Revolutionary War and had been paid by grants of lands on the frontiers. By forming militia units they enabled the younger militia men to go off to war while they stayed to protect the local settlements. Like the Home Guard in Britain during the Second World War, they did provide a valuable reserve in a time of crisis.

This Veteran Exempts flag may have been used at the Battle of Plattsburgh in upper New York. The Battle, also known as the Battle of Lake Champlain, ended the final British invasion attempt of the northern United States during the War of 1812. Fought shortly before the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, the American victory denied the British leverage to demand exclusive control over the Great Lakes and any territorial gains against the New England states. Little other information is available on the activities of the Veterans Exempts during the War of 1812.

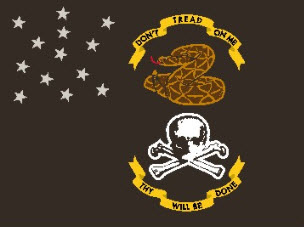

The Veterans Exempt flag was described in the Plattsburgh Republican, July 31, 1812, as having "...a black ground with 13 stars for the Union of White, wrought in silver. That in the centre of

the Flag there he a Death's Head, with cross bones under, intimating what must soon, according to the course of nature, be their promiscuous fate, and the immediate one of any enemy who shall venture to contend with them. Under these an open wreath, with this motto, ´Thy will he done.´ Over the Death's Head, surmounted as a crest, a Rattle-Snake with Thirteen rattles, coiled, ready to strike, with this motto in a similar wreath inverted over it, ´Dont tread on me.´"

|

First School House Flag

|

The Colrain School House Flag 1812

In 1812, a US Flag was first raised over a school house on Catamount Hill in Colrain, Massachusetts. It wasn't until after the Civil War that flying the flag at schools and other public buildings became a general practice. Flying this hand-made 16-star flag was, as far as we know, the first known instance of a flag being flown at a school house, and predates the Civil War by almost 50 years.

This may be yet another first for the State of Massachusetts. |

20-Star Flag

20-Star Flag variant

|

The Twenty Star Flag 1818

In 1818, five stars were added to the flag, representing Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, Ohio, and Tennessee, bringing the total number of stars to 20.

On April 4, 1818, an act was passed by Congress at the suggestion of U.S. Naval Captain Samuel C. Reid, in which the flag was changed to have 20 stars (with a new star to be added in the future when each new state was admitted), but the number of stripes would always remain at thirteen to honor the original colonies. The act specified that new flag designs should become official on the first July 4 (Independence Day) following admission of one or more new states.

However, there was no provision for how the stars should be arranged (that was not cleared up until 1912). The military services, however, did establish regular patterns as early as 1818, but these were not binding on the public. Stars in rows were, of course, the most common design for commercially manufactured flags as it was the simplest to produce. |

First Great Star Flag

|

The "Great Star" Flag 1818

This 20-star flag flew over the Capitol dome for six months in 1818. There have been many suggested "Great Star" designs over the years. The first most people know about was the Peter Wendover/Samuel Reid's proposal to have the U.S. Flag bear the stars in a "Great Star" pattern for use on land and on private ships and in rows for the navy, proposed in 1818. Congress did not accept this idea; in fact, Congress purposely did not specify how the stars were to be arranged. |

24-Star Flag

Old Glory

|

"Old Glory" 1822

This first period of American flag history would not be complete unless we included the flag that coined the phrase "Old Glory." When Missouri became the twenty-fourth state to joined the Union a new flag was approved. For the next 14 years this 24-star flag would proudly wave over the United States until 1836. Although the nickname "Old Glory" has now become common for all US Flags, at first it refered specifically to a flag from this period owned by a Salem, Massachusetts, sea captain named William Driver. Old Glory was hand-made for Captain Driver by his mother, sometime around 1823.

This 24-Star flag measured 10 feet by 17 feet and was designed to be flown from his ship's mast, had 24 stars, including a small anchor sewn into the corner of its blue canton. The proud captain began calling his flag "Old Glory," taking the flag around the world several times in his whaling vessel the "Charles Doggett." Driver retired in 1837 and moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he flew his beloved flag on all patriotic occasions, using a rope suspended across the street, and Old Glory became a well-known sight for the people of Nashville. By 1861, he had modified it to show 34 stars, but had to hide it when Tennessee joined the Confederacy. When Union forces retook Nashville, Driver brought out his flag once again and it was raised over the state capitol. The 6th Ohio Infantry, which was present at the ceremony, soon adopted the name "Old Glory" as their motto. The whole story was picked up by the newspapers, and eventually the nickname of Old Glory become one used for all US flags. |

- My thanks to Jack Barrette and James Ferrigan for their expert help on this page -

| Top of Page | Flags before 1776 | Flags after 1776 | Unit Standards and Colors | War of 1812 |

|